The unintended consequences of turning down the thermostat this winter

The unintended consequences of turning down the thermostat this winter

According to the Energy Information Administration and their Winter Fuels Outlook report, it will cost 27 percent to 28 percent more than 2021/2022 to heat your home with oil or gas. If you heat with electricity, prices may rise by as much as 10 percent, because much of our electricity is generated from oil and gas. (Newsweek.com)

When you have a fixed or unstable budget, the decision to lower or turn off heat during the winter is not easy. The other components of our budgets–food, housing, transportation and medical care–aren’t as flexible as those extra blankets, mittens and hats, so down the thermostat goes. This is where what you don’t know might hurt you.

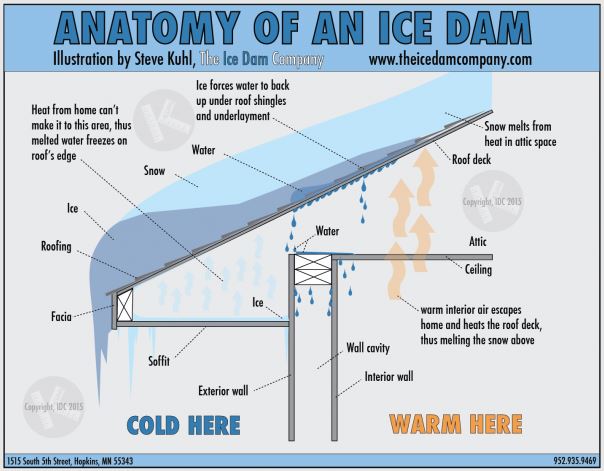

It’s not only the air temperature that changes when the heat source turns off. Air holds a certain amount of water vapor, also called humidity, and warmer air can hold more water vapor than cooler air. When the air cools, water vapor in the air will tend to condense on any surface that is lower than the dewpoint temperature. That’s why you see condensation on windows and around door frames in winter: these are the points that tend to conduct cold temperatures from the outside, and moisture from the air is condensing on them. Persistent moisture is mold-feeding moisture, and before you know it, there is a mold problem. Even worse is that mold could be forming in places you can’t readily see, like inside walls, attics and basements, because the air temperature has dropped and cooler air just can’t hold the moisture of warmer air. Cooler air can easily reach humidity levels of 80% or more, giving that “damp” feeling and over time, exposing the home to mold growth.

There is a myth that when a room is not being used, it’s best to turn off heat (close registers) and close it off from the rest of the house (close the door) to save money. If this is done without any ventilation or air circulation, it’s also a recipe for mold, because without air circulation, water vapor in stagnant air will be absorbed by furnishings and allow mold to take root. If you need to limit heating in your home, try to leave doors to unused rooms at least cracked and leave a fan running in the room, because dynamic airflow limits moisture ingress due to evaporation. For more on finding and fixing areas prone to mold in the winter, check out our article.

If high humidity is not a problem, low humidity might be. Low humidity can damage all kinds of decor in your house by shrinking and drying, from wood flooring, wallpaper, and furniture to fine instruments like pianos and guitars and artwork.

Then, there’s your body. Stress due to cold is a real problem for the elderly and those with pre-existing medical conditions like asthma or heart disease. It also makes people more likely to use alternate heating methods that could be unsafe. Small room heaters are often known to tip over and cause fires, and electric blankets can actually cause burns. Falling asleep on a bunched-up blanket is a common cause of burns, according to Bell, a plastic surgeon who treats many burn patients. He explains that when a hot blanket rests on the same body part for an extended period, the skin can burn. “These burn accidents usually happen because someone has fallen asleep on a bunched-up area of the blanket,” he says. Unfortunately, people with diabetes are more vulnerable to burns from electric blankets because their condition makes them less sensitive to heat. “Electric blankets are also not recommended for infants, young children or anyone who is paralyzed or incapable of understanding how to safely operate them,” says Bell. People with urinary incontinence also should not use electric blankets because wetness and electricity don't mix. (ul.com) If you do use an electric blanket, follow all the safety guidelines of UL Solutions (previously Underwriters Laboratories) so that you don’t become one of these statistics!

When home heating costs rise, air quality can also worsen due to particulates in the air. In Europe, the impacts of inflation and fuel scarcity due to the Russian-Ukrainian war is particularly hard on middle and lower income families, and they turn to alternative sources like burning wood, coal and even garbage in indoor stoves. These stoves impact indoor and outdoor air quality. Indoors, reloading a stove that is already burning fills the air with particulates, and combustion gasses can leak out of improperly-sealed doors and exhaust pipe fittings, exposing inhabitants to dangerous levels of carbon monoxide and particulates. Outdoors, European cities that typically have poor air quality during the winter may have even worse this winter. A recent study from Greece showed that wood burning was responsible for almost half of the cancer-causing air pollution in Athens and a new study from New Zealand has showed an increase in serious respiratory infections when wood smoke built up in an area. (TheGuardian.com) If you live in one of these areas, it doesn’t matter whether you are the one burning wood–you will still be breathing its effects.

If you feel financial pressure to lower the thermostat this winter, here are some practical ways to keep the air warmer and less humid in your home (Prof Cath Noakes from the University of Leeds):

- Move seating away from cold windows

- Use thick curtains at night, but allow the sun to come in during the day

- Ensure radiators or ventilation registers are not covered or blocked by furniture

- Ventilate using high-level windows can reduce cold drafts

- Ventilating after a shower or when cooking can prevent moisture buildup which can lead to damp and mold.

It’s sometimes harder to detect high humidity in the winter because of the lower temperatures, so don’t take a risk–keep one or more humidity sensors in your home for monitoring it. Our bipolar ionizers like the Germ Defender, Air Angel or Whole Home Polar Ionizer actually deter mold even if humidity temporarily goes too high, making them great investments for all seasons.

Finally, if you have a warm home, sharing it with your elderly, disabled or disadvantaged friends for a meal or a few hours could make a huge impact in their lives. Helping them to purchase safe heating appliances and understand how to keep humidity at manageable levels also will help them to live healthier. Warmth is not always about containment, but allowing it to radiate to others.