Lime: an ancient wonder-mineral

If you read our article on Ancient Homebuilding 101, your interest might be piqued about lime and its use as an anti-fungal coating inside and outside homes. We gave a number of benefits of limewash that are still used on some farms and buildings today; if you see white walls inside a dairy barn, for example, it’s most likely limewash. But how does limewash work to kill germs? The answer lies in its chemical makeup before it’s completely dry, and repeating the application.

Mold does not grow on limewash when it’s fresh. Here is advice from Timothy Sly, a Food-borne disease epidemiologist. To make lime-wash, quick-lime (calcium oxide, CaO) is ‘slaked’ with water to produce calcium hydroxide, Ca(OH)2. A slurry of this is applied to the wall, stone, plaster, etc. It begins as a strong alkali (base), but after a while, atmospheric acids (e.g. carbonic acid, H2CO3) react with the slaked lime to produce a neutral carbonate (CaCO3). At this stage, though still white, the surface can support molds and mildews that use pollen , soil, and other dust as a substrate. The solution is to apply more lime wash at LEAST once a year, often twice.

When lime-wash was applied frequently and regularly to house-roofs in the tropics which were - and still are - used as rainwater catchments, the water collected was partially protected with the bactericidal effect of freshly-slaked lime. But as modern options appeared, house-holders chose to use white latex paint on their roofs, which now required re-painting much less often. The problem was that all the bactericidal effect was now absent, and the water in the collection cistern was of a poorer bacterial quality, grew more algae, and had more mosquito larvae present. Another example of ‘improving’ A only to cause more problems with B.

Lime render and mortar physically degrade because of chemical removal of the calcium ions by dissolved atmospheric acidic gases and by chemical substitution with sulphates and chlorides. As erosion occurs, spaces form in the lime providing damp niches for chemotrophs (organisms like mushrooms or bacteria which manufacture their food from inorganic substances in the presence of energy derived from inorganic compounds) which produce toxic compounds of ammonia and nitrite salts and as they die, form a nutrient base for other organisms. (Novel Biodesign enhancements to at-risk traditional building materials)

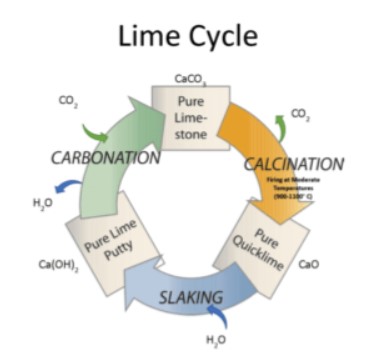

Here is a rendering of the “Lime Cycle” (from LimeWorks.us)

This diagram shows that it’s really a layer of “limestone” or CaCO3, that is formed when you limewash and allow it to dry (top of diagram).

Let’s take that cycle one step at a time. The following is adapted from Calcium carbonate and the Lime Cycle. Calcium carbonate is a very common mineral in the Earth's crust. It is the main building block of most animal shells, including the shells of shellfish, snails and birds’ eggs. There are four main types of rock containing calcium carbonate: limestone, marble, chalk and calcite.

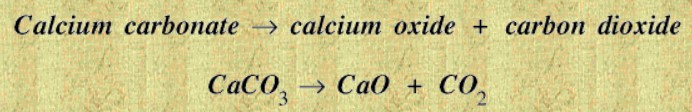

If we heat limestone to a very high temperature (to about 900 degC or 1652 degF), it decomposes - this is an example of thermal decomposition.

Calcium oxide is known as lime, or sometimes quicklime. If we heat a lump of quicklime very strongly it gives out a very bright white light. This is known as limelight. Limelight was used for stage lighting before the introduction of electricity, so famous actors and actresses were said to be in the limelight.

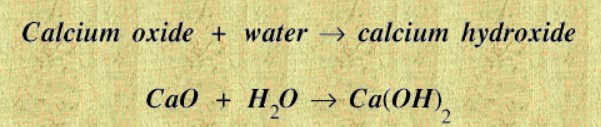

Quicklime reacts very violently with water giving out a lot of heat.

This reaction is called slaking. Calcium hydroxide is also known as lime, or sometimes slaked lime.

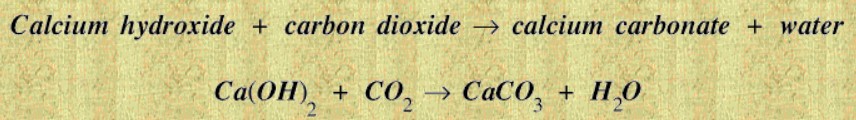

Lime mortar hardens as it dries. In addition a chemical reaction takes place between the lime and the carbon dioxide in the air.

This reaction takes place quite quickly at the surface but more slowly in the interior: not all of the lime in the lime mortar used to build the Great Pyramid has yet turned into calcium carbonate - after more than four thousand years! The carbonation process absorbing atmospheric CO2 occurs at about 5 mm per month from the outer skin working inwards. (Novel Biodesign enhancements to at-risk traditional building materials)

As you can see, processing limestone is a very energy-intensive process, but when compared to manufacturing Portland Cement, it’s actually more energy efficient. Although it doesn’t actually sequester carbon (because CO2 is released during the burning process and it’s reabsorbed during the curing process), it does produce less CO2 emissions than Portland Cement. During manufacture lime produces 20% less carbon dioxide than cement production. Lime is burnt at a lower temperature than cement in the production process (900°C as opposed to 1300°C), therefore making lime production more economic. (The History of Lime and its Environmental Benefits) In addition, cement does not “reabsorb” CO2 and is brittle (cracks), while lime used in cement can somewhat “heal” cracks. If “lime putty” is added to mortar, it makes it more breathable (permeable) than Portland Cement (check out the pore structure here).

Lime’s anti-fungal properties can also be used on living trees, to protect trees from disease, sunburn and frost injury: The National Park Service used it on their historic trees, and it’s also recommended for citrus trees by a knowledgable tree service.

If you want to use lime inside your home to deter mold or remediate a moldy area, Earth Paint has taken a 10,000 year old technology and engineered it to be safely applied directly over high moisture content, Mold and Mildew stained surfaces. This product uses the power of lime to penetrate and saturate the porous cell structure of wood, drywall and concrete matrix. As such, spray coating your building with Lime Prime and Lime Seal renders a weather and air barrier outside. Inside, before windows and drywall are hung, spraying the frame and wall cavities with Lime Prime will inhibit mold inside the walls. (Lime Prime - Mold Abatement / Remediation)

For more benefits of limewash, be sure to visit our article on Ancient Homebuilding 101. Lime is everywhere…did you also know that calcium carbonate is also the primary ingredient in antacids like TUMS? You also may be walking on it or showering in it, because travertine is really a type of limestone. It just goes to show that limestone is not just for caves; it’s a really useful (and beautiful) material in many aspects.

Photo by Anne Nygård on Unsplash