What’s the difference between dangerous mold and good fermentation?

What’s the difference between dangerous mold and good fermentation?

Maybe you’ve heard about fermented foods as one of the latest health fads, and are wondering (like I was), what’s the difference between green cheese discovered in the back of the fridge, and “good” stinky cheese, kombucha or sauerkraut? They all seem to use microbes to change the flavor, so how can we tell the difference?

Fermented foods are defined as “foods or beverages produced through controlled microbial growth, and the conversion of food components through enzymatic action” (my emphasis, from 2016 study). The main difference, it turns out, is the intention and methods (control) of allowing food to ferment. Fermented foods have been around for a loooong time. When you have foods that are notoriously difficult to preserve (dairy) in a hot climate (the middle east and Africa), fermentation happens naturally and quickly. As long ago as 10,000 BCE, people figured out how to control the natural bacteria present in cow, sheep, goat and camel milk to produce yogurt. This is called “thermophilic lactic acid fermentation”. (Living History Farms) This continued for centuries and in 1910, a Russian bacteriologist, Elie Metchnikoff, attributed the longer average lifespan of Bulgarians (87 years) to increased fermented milk consumption, and a particular strain of bacteria used in their fermented milk products. Certain strains of “Lactobacillus bulgaricus” were shown to be able to survive and flourish in the human stomach and intestines, making them the first “probiotics” discovered. Probiotics simply are live bacteria and yeasts that are good for you, especially your digestive system. (webmd.com) The “cultures” of live bacteria and yeasts in fermented foods make them full of natural probiotics. However, ancient peoples (through the 1900s) were likely not eating them for their health benefits. Fermenting was simply a form of food preservation. Cheese, bread, vinegar and beer are all products of fermentation. Food can be fermented naturally using the microbes that are present in the food itself, or by adding a “starter culture” that has the desirable microbes included. (2019 paper)

Many studies have been conducted on the health benefits of fermented foods. Some have been proven, and others are disputed. For example, compounds known as biologically active peptides, which are produced by the bacteria responsible for fermentation, are also well known for their health benefits. Among these peptides, conjugated linoleic acids (CLA) have a blood pressure lowering effect, exopolysaccharides exhibit prebiotic properties, bacteriocins show anti-microbial effects, sphingolipids have anti-carcinogenic and anti-microbial properties, and bioactive peptides exhibit anti-oxidant, anti-microbial, opioid antagonist, anti-allergenic, and blood pressure lowering effects. (paper investigating the health effects of fermented foods). As a current health hot topic, it’s best for you to do your own research on any fermented food you want to start including in your diet.

There are many types of fermentation that are culture-specific, having such a strong smell and/or taste that to the uninitiated, may be called “rotten”! In fact, “one person’s delicious fermentation is another person’s disgusting rot, and according to fermentation guru Sandor Ellix Katz, “Learning a sense of boundaries around what it is appropriate to eat is necessary for survival. But precisely where we lay those boundaries is highly subjective, and largely culturally determined.” (americastestkitchen.com) This is the case for hákarl, an Icelandic delicacy often referred to as “rotten shark”, Surströmming, a Swedish fermented herring product, natto, a slimy fermented Japanese soybean dish, and century eggs, which are fermented for 3 years in some Southeast Asian cultures. (18 stinky foods around the world).

Okay…we know that heat and microbes will break down food whether or not we initiate it, so just what kinds of “control” can we exert over fermentation?

One key is just as invisible to the naked eye as the microbes themselves: air. Fermentation is generally an anaerobic process, which occurs in an airless environment. Most desirable bacteria thrive in this oxygen-free environment digesting sugars, starches, and carbohydrates and releasing alcohols, carbon dioxide, and organic acids (which are what preserve the food). Most undesirable bacteria that cause spoilage, rotting, and decay of food can’t survive in this anaerobic environment. (Living History Farms) Unfortunately, this reference does not point out at least one major exception: Clostridium botulinum, which produces botulism. In order to keep vegetables from developing undesirable mold, for example, they are “weighed down” under the fermenting liquid so the food does not contact the air.

According to Paul Adams, a researcher for America’s Test Kitchen, we have a few other tools to keep the fermented product safer and less smelly: salt, temperature and acidity. For example, allowing cucumbers to sit in room temperature water will usually produce a scummy pink slime in short order, but changing the water for brine (saltwater) will produce some nice tangy pickles. Brewing beer has its best results when controlling the temperature, so brewers have developed methods to decrease or increase the temperature of their kegs depending on the ambient air temperature. Finally, acidity is a tool for controlling fermentation. pH is the measure of acidity or alkalinity in a solution and pH changes due to changing chemical composition produced during fermentation. pH also can control the species of microbes in fermentation. For example, the low pH (acidity) of kombucha, owing mainly to the production of high concentration of acetic acid, has been shown to prevent the growth of pathogenic bacteria such as Helicobacter pylori, Escherichia coli, Salmonella typhimurium and Campylobacter jejuni. (2019 paper) According to Utah State University Extension Service, for fermentation to be successful at eliminating all potential pathogens, the pH level must drop below an acidity of 4.6 verified by using a pH meter or test strip. Foods that “appear” to be safe can still contain harmful pathogens.

What’s the difference between yeast and mold?

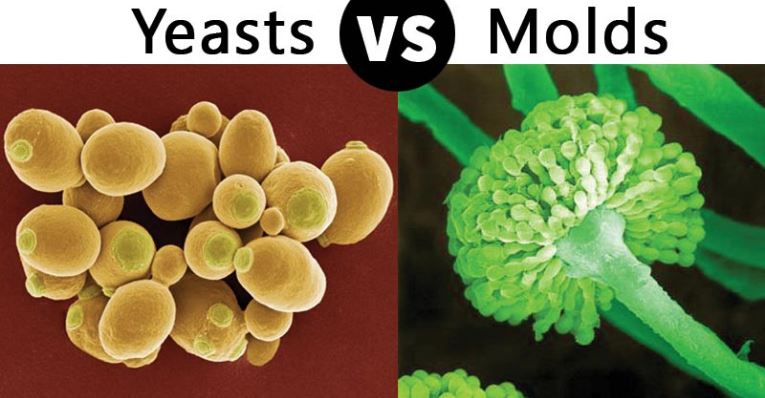

Yeasts and mold are both considered fungi. Yeasts are microscopic fungi consisting of solitary cells that reproduce by budding. Molds, in contrast, are multi-cellular and occur in long filaments known as hyphae, which grow by apical extension (extending into fresh substrate). Yeasts do not produce spores; molds do. Yeasts can grow in aerobic (with air) or anaerobic (airless) conditions; molds only grow in aerobic conditions. Regardless of their shape or size, fungi are all heterotrophic (cannot produce their own food) and digest their food externally by releasing hydrolytic enzymes into their immediate surroundings (absorptive nutrition). (Introduction to Mycology textbook) Here is a highly magnified photo of the two:

Photo source: microbenotes.com

As a company concerned about air quality, HypoAir is typically anti-mold except where it’s cultured and processed carefully for medical and gastronomical reasons (like penicillin and cheese)! Penicillium (P.) roqueforti, P. glaucum, and P. candidum are some common types of mold that are used in cheesemaking. (thecheesemaker.com) I’ve found out through researching this article that there are other types of mold that give fermented food its characteristic flavor and possible health benefits. For example tempeh, an Indonesian fermented soybean cake, and Miso, a traditional Japanese paste of fermented soybean used to make miso soup, both contain molds that have no detrimental effects to humans. Likewise, yeasts are familiar to those who make bread, but Kombucha, a fermented tea beverage reported to have originated in northern China, is also made with yeast. The critical aspect of making each of these foods is providing the correct environment, including temperature, pH, humidity and salinity, to encourage the good fungus and discourage bad fungus!

Of course, there is a lot of information on the internet about making fermented foods at home. Not all of them advise the safeguards that are necessary to prevent harmful bacteria from giving you life-threatening food poisoning, so it’s best to compare them to a source such as the USDA. For example, this guide on safely fermenting food at home recommends starting fermentation only on fresh, clean vegetables and using non-iodized salt. In addition, the National Center for Home Food Preservation has tips and tested recipes.

If you have any doubts about the safety of fermented food, throw it out! The website fermentools.com gives the following advice on when to do so:

- Visible fuzz, or white, pink, green, or black mold.

- Extremely pungent and unpleasant stink.

- Slimy, discolored vegetables.

- A bad taste. If your taste buds are offended, be safe and spit it out!

If you follow the safety guidelines, you can explore the world of fermented foods and maybe even make your own food combinations to surprise family and friends! (Who wouldn't like a delicious jar of well-preserved food?)

Photo by Brooke Lark on Unsplash