Why is my house so DUSTY? Assessing the air currents gives a clue

Why is my house so DUSTY? Assessing the air currents gives a clue

This article was written in response to an actual problem. My elderly parents moved into a “barndominium” which was converted from a 35x35’ metal workshop, in 2020. The walls were insulated with fiberglass batts, and the attic above their 10’ ceilings was insulated with blown-in insulation. I listened to my mom’s complaints about dust in the house. This is a real problem because the dust seemed to settle very quickly after cleaning, and my father has COPD. Since the dust seemed to be a whitish colored dust, together we decided it must be coming from the attic, which had extra (white) insulation blown in after renovations were complete. We increased the HEPA filtration of the HVAC, with no results. I checked for openings in the flexible ducts of the HVAC which could entrain insulation, with no results. I tried several different times to seal the attic penetrations, which in actuality should have been done by a conscientious insulation company BEFORE the extra insulation was blown in. I sprayed foam:

- Around the HVAC vents

- Around the bathroom exhaust fans

- Around the LED puck lights (must check with the lighting manufacturer before doing this as some lighting is incompatible with direct-contact insulation. The light needs to be “IC rated” in order to safely come into contact with the insulation.)

- Around ceiling fan boxes

- Around hanging shelf penetrations through the drywall of a floor-to-ceiling closet

It took multiple trips to the attic (with a good dust mask, of course) and quite a few cans of spray foam to get the job done, but sealing these areas, and one other (big) thing really helped cut the dust down. It wasn’t until I really analyzed what was propelling the dust from the attic into the living space, that I figured out what was going on.

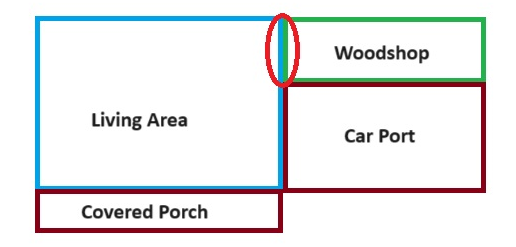

We’ve written several articles about negative pressure in your home and its negative effects. (This one has an eye-opening video linked). I suspected that the dust was coming from the attic because negative pressure was somehow being generated in the house by the HVAC system. However, I didn’t look at the big picture. The living space is adjacent to a woodshop where my father carves (his hobby) and he uses a powerful dust collector to whisk the dust out of the workshop to a drum container. The motor on this dust collector is rated for 240V so you can imagine that it’s a heavy-duty machine and being situated in the carport, can be heard from some distance from the house. This thing SUCKS, and most of the time he’s using it with the door and window closed, so where is the makeup air coming from? The workshop shares a common wall with a small bedroom in the living area (see red circle in diagram below). It’s not too big of a leap to think that the dust collector may be pulling air from the house, as well, which in turn draws air from the attic when the ceiling penetrations were not sealed.

To seal the wall between the woodshop and living area, I caulked the baseboard to the floor, as well as sealed the electrical boxes by taking off the switchplate and sprayfoaming around them as much as the little foam straw would allow (extra large switch plates help if you have to cut out the drywall a little). The drywall took care of the rest of the wall.

Sometimes it takes a bit of thought to figure out the air currents in your home, but they are well-worth investigating! Recently I found (by accident) that some carpenters had terminated a whole-house vacuum system in the ceiling of their house instead of routing it outside. Even though the system used a filter, the space above the tiled ceiling was thick with a fine dust. We only discovered it when a leak forced replacement of part of the roof above it. We extended the PVC vacuum exhaust pipe just a few more feet and ran it out through the soffit. It just goes to show that a little investigation (and a lot of spray foam) can go a long way to maintaining less dust in the house!

Photo by Kent Pilcher on Unsplash