Wait–I thought mold was only a problem during the summer!

Wait–I thought mold was only a problem during the summer!

When humidity levels in your home plummet during the winter months due to dry outside air and even more drying heated air inside, it’s easy to think that mold could not possibly be a problem during the winter. We’re sorry to have to debunk that myth, but sadly mold is a year-round problem! It flourishes in environments between 60 and 80 degrees and can grow wherever moisture or humidity is present. It’s a problem in the winter because it can grow in your walls and attic, places where it’s hard to detect. (Maryland HVAC company Griffith Energy Services)

Why does mold occur during the winter and where does it get the moisture to grow? The answers lie in temperature differentials and air leaks. Warm air that escapes the building envelope can cause condensation when it hits a cold surface (heat energy travels from hot to cold areas). The worst part is that many of these unregulated “meeting places” of warm air and cold surfaces are deep inside your walls, attic, basement or crawlspace, going undetected for months until it becomes a BIG problem. Here are some specific problematic places:

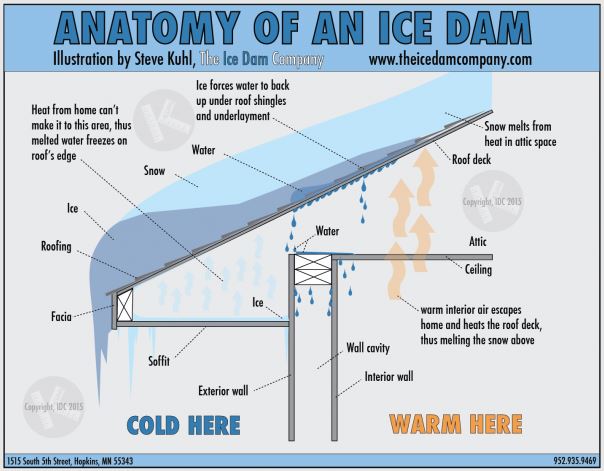

- Do you have ice dams on your roof? Ice dams occur near the bottom edge of a roof, and they are formed when snow melts on the roof above your attic (usually due to missing or insufficient insulation), runs down the roof to the edge and refreezes, causing a buildup of ice at the edge of the roof. The ice can even force its way underneath shingles and sheathing, and when it reaches the attic space, will melt again and “rain” in your attic! The condensation can drip onto insulation, run down into cavities, and cause a lot of mold. It’s quite a damaging problem in any climate that can get freezing weather and precipitation; even just a dusting of snow can form an ice dam. Plugged gutters that fill up and freeze can also form ice dams if they are too close to the roofline. Here’s the “anatomy” of an ice dam:

Source: icedamcompany.com

- Plumbing pipes that run through poorly insulated walls can create a cold surface on which warm air from the home can condense.

- Glass is not a great insulator; a single-pane window will have an R-value of 1 and the standard double-pane window will have an R-value of 2 (see our article on insulation for an explanation of R-values). Warm air inside condenses on that cold glass, and condensation that runs down windows can pool on the wooden jambs and framework, allowing mold to grow.

- The basement is another place where there is often high humidity, and windows, steel doors and penetrating pipes can be cold surfaces on which condensation will form, which mold loves.

How can your dry indoor air hold so much water vapor to make condensation? It doesn’t seem possible until you consider the dewpoint. It’s true, air at 50% relative humidity does not have enough moisture to sustain mold growth. The answer lies in the dewpoint of that air. Check out this fun dew point calculator (well, I think it’s fun and incredibly useful!) Make sure that the little blue dot is set to solve “dew point” and the units are set to deg F (or deg C if you are used to Celsius). Now, use the little sliders to adjust the temperature and humidity to your normal indoor environment (get one of our humidity sensors if you don’t have one!), and watch how the dew point changes. For example, 75 degF at 50% relative humidity = 55 degF dew point. That means that any surface below 55 degF can cause water vapor to condense out of your “dry” air! If you put your hand on a single pane glass window when it’s snowing or freezing outside and warm inside, I’m sure you’ll agree this could be a potential problem.

How can we prevent winter mold?

Look up and pay attention to your ceilings, upper stories and attics. Since heat rises, it makes sense that the warm air from your home may cause the most problems in your upper parts of your home where warm meets cold. Humid air will accumulate in the upper areas of your home right along with the heat. Bring your humidity sensor upstairs (if you have a 2nd story on your home) and note the increase.

- Seal around can light fixtures and other openings in the ceiling.

- Cathedral ceilings are especially prone to mold, because the heat and humidity rise high in your home and hit the roofline (typically there are no attics above cathedral ceilings) that may be poorly insulated. (Check out these videos by a mold restoration company in Kansas City). If you replace your roof, consider increasing insulation in cathedral ceilings either by spray foam, or adding rigid foam boards above the sheathing. Here’s an article by a building science expert on how to install rigid foam boards in roofing.

- Make sure ceiling fans are moving counter-clockwise during the heating season, to draw warm air down.

- Seal the attic stair hatch (if you have a collapsible attic stairway) with a zippered or velcroed containment like this one, which can also save money on your heating bill. If you have an attic access that is simply a hole cut in your ceiling with trim and loose-fitting plywood or drywall above it that you lift up to get into the attic, try to find a way to add weight to the piece of drywall or plywood (so it sits down snugly) and seal the edges with foam weatherstripping so that gaps don’t let air through.

Mold sometimes forms in plain sight during the winter. Often bedrooms that are not used are closed off from the rest of the house, but lack of ventilation can be a recipe for mold. It’s best to open the door and turn on a fan in the room to prevent mold growth on cold corners and walls. Be vigilant to check north-facing walls, corners and closets, as these can be the coldest in your home. If you discover mold in a closet, check out our article (see #6) for tips on keeping it mold-free once it’s been cleaned.

If you have single-pane windows, you don’t necessarily have to replace them to “up” their insulation or R-value and avoid the condensation that can lead to mold. Here are a couple of solutions:

- Insulated drapes can prevent warm air from hitting cold windows–just make sure they go all the way to the windowsill or floor and fit closely along the sides, to make a “seal”.

- There is conflicting evidence whether window films (that are cut and fit to “cling” to the glass of your window) and shrink-fit window insulation actually reduce condensation on your windows. This article by an Australian company brings up two important points: that radiant energy will still flow through the window film, and the air-tight seal required for the shrink-fit system to work will seal moisture into the space between the window and film (not good). If condensation is a problem on your windows, it’s not clear whether these two solutions will work.

- “Indows” are inserts that fit inside your windows (how clever is that name!). They are custom made from measurements you provide and fit snugly against the frame with compression seals and are supposed to increase the R-value of single pane windows to 94% of double-pane windows. This short video shows a customer measuring and fitting his new Indow.

Even if you don’t plan to replace siding on your home, there are companies that can increase your exterior wall insulation in discreet ways so that mold doesn’t form inside walls. It may be possible to add insulation between the studs by either removing a layer of siding at the middle or top of the first floor, or drilling through the interior wall. Then loose fill or spray foam can be blown into the cavity, and the siding replaced or the hole patched. (attainablehome.com) Loose fill can be sheeps wool, cellulose, fiberglass, hemp, cork or a mixture of agricultural products, like ClimaCell.

Make sure you check the basement regularly to ensure that everything is dry, so that you won’t be surprised by mold. We have a lot of tips on preventing mold in the basement in this article.

Finally, suit up with some warm layers and take a walk around your house to see where cold air might be seeping in from the outside. Evidence of animal intrusion, missing siding, fiberglass insulation peeking out, missing shingles, and exterior mold or rot are all areas to address. Don’t let dry winter air fool you, because unregulated “meeting places” of warm air and cold surfaces can produce moldy consequences!