How do older homes compare to newer homes?

How do older homes compare to newer homes?

According to Realtor.com, older homes are those that are not built with modern building materials like high-performance concrete; typically they were constructed before the 1970's.

Many older homes can be purchased at a discount because they have not been “updated”. These updates of course include aesthetics like granite or marble counter tops, as well as necessary systems like modern electrical wiring, HVAC and plumbing. Aside from the normal aspects that buyers of older homes will want to renovate, what are the hidden pros and cons that come with older homes?

Arguably, construction and maintenance of the roof and foundation of older homes may have the most to do with the condition it is in today.

Older roofs can be much more durable, as well–here are the lifespans of typical roofs according to their materials (“composite” means the fiberglass-and-asphalt shingles which are on 80% of US homes today):

Not included is the asbestos shingle, which is estimated to last 30-50 years. (nowenvironmental.com) Although this is a reasonably durable material, due to its health problems (fibers exposed to the air can be breathed in, causing disease), asbestos tiles are no longer sold for repairs, so an asbestos roof would likely need replacement. (rooforia.com)

In addition to the longer lifespan of older roofing materials, there is the underlayment–what the roof is attached to. Before plywood and oriented strand board (OSB) were available, sturdy “two-by” boards such as 2x6 or 2x8’s were used over rafters to provide the base for applying a roof. These were much more durable during severe weather, and more durable in terms of rot and deterioration. Of course, they are not used in most modern homes because of cost; homeowners would rather invest more money in something they can see!

Older homes also typically had the benefit of larger roof overhangs. Prominent overhangs do several things that increase the longevity of the house: they deflect sunlight and UV damage from the windows and walls, and protect the same areas from rain and water intrusion. Skimpy overhangs in modern construction do not do either!

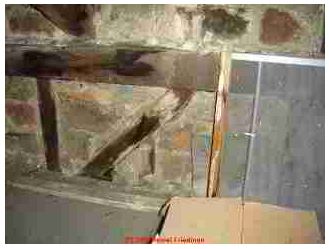

Foundations of older homes (before concrete slabs were widely used) could be good or bad, depending on the method of construction and materials. Here are some foundation materials commonly used (inspectapedia.com):

Wood, beams set on grade or on flat stone set on or close to ground level (older, very susceptible to rot and damage)

Stone, natural found on site or brought to the building site (older, susceptible to movement and settling)

Brick, less commonly used below grade, more often used from grade-level up, set on stone below grade. (older, susceptible to movement and settling)

"Cinder blocks" or concrete blocks (from early 1900’s, persistent through today for smaller homes)

Poured concrete (poured concrete footings as early as 1912; wisconsinhistory.org)

Pre-fabricated concrete foundation sections assembled onsite (since early 1900’s)

Wood, treated lumber, treated plywood on treated wood or on concrete studs (also used today for smaller homes)

Obviously, the quality and maintenance of the foundation determines the condition of the home. It didn’t take an earthquake to start a home into deterioration; one groundhog can make a burrow that will damage a pier and cause the house to lean and crack, allowing water intrusion.

Subfloors: A floor with particle board or even higher-quality plywood as subflooring under carpeting won't feel as sturdy as one that's made from multiple layers of solid boards laid diagonally, an old technique that's now prohibitively expensive. (washingtonpost.com)

Insulation has certainly evolved over the last 50 years. This includes the addition of air and vapor barriers, and types of insulation. If you don’t have the opportunity (or burden) of getting down to the studs to re-insulate an older home, it could be quite uncomfortable in extreme weather like deep winter or summer. However, some features of older homes actually had fairly “air-tight” construction. Examples include multiple layers of lath and plaster, brick wall “insulation” or “nogging” where brick was installed between wood framing to block the wind, or a small 1" air gap is also found in older structural brick walls; the air gap in brick walls was intended to avoid transmission of moisture from outside the building to its interior. (inspectapedia.com) Modern insulation makes all the difference in comfort, however, when it is properly installed.Construction materials: Even the wood of “stick built” homes has changed. The change has to do with the loss of “old-growth” forests in the US, where trees were between 100 and 500 years old. By 1940, old growth lumber was not available for construction anymore, and lumber came from younger trees. Today's building lumber is made from trees that are between 12 and 20 years old. These trees have fewer growth rings per inch than old-growth trees. Older trees have more dense wood, which is also more rot-resistant. (WisconsinHistory.org)

Old-growth lumber may not be available anymore but naturally insect-resistant trees, provided they are sustainably harvested, are significantly more ecological and healthy than pressure-treated lumber. Western Red Cedar and Redwood have unique compounds within the cells of the heartwood that protect against insect and water damage. They usually only require topical treatments for coloring or sealing. (thinkwood.com)

Before the 1920’s, “2x4” wood studs were actually 2” by 4” in dimension. After that time, dimensions varied and ended up at 1-½” x 3-½” as the standard since 1964. Even though you may think wood is old-fashioned, flammable, inferior to steel or concrete, or too pricey to use it for interior design such as timber-style construction, architects are using it in new ways for safety, strength and design. “Mass Timber” is a new style of design in which wood is used for large commercial and residential buildings. It’s appropriate since wood has many biophilic benefits that can contribute to the health and well-being of building occupants. (thinkwood.com) New methods of laminating wood such as cross-lamination, nail-lamination, dowel-lamination and glue lamination, makes it strong and able to span long distances, as steel girders and concrete do. The laminating adhesives and fire-retardant treatments of such products are the main concerns for use of these products, however if they follow industry-standard manufacturing practices such as ANSI A190.1 (Product Standard for Structural Glued Laminated Timber) then it should be naturally low in VOC emissions such as formaldehyde. (anthonyforest.com)

Construction methods: Kit vs. Pre-fab vs. on-site

Although “kit” homes were originated in the UK in the late 1800’s and became popular in the US in the early 1900’s, they were very different from the pre-fab homes of today. Kit homes, like pre-fab homes today, were offered to make housing more accessible. One Sears catalog assured that “anyone with rudimentary skills could have their home built in 90 days.” (thecraftsmanblog.com) Many kit homes from the early 1900’s are still standing today and demand a premium in the housing market, a testament to the quality of materials and design in these homes.

However, the quality of pre-fab homes today do not resemble that of kit homes because they are built off-site and transported in large pieces to the building site, then assembled. "They don't build them like they used to--and a lot of that comes in economics, labor versus material costs. Historians have documented, beginning in the 19th century, labor costs going up and up, and material costs going down and down. Now, we're in a time when bringing someone on site to do the work is the expensive part, not the material." –Bill Dupont, an architect who works for the National Trust for Historic Preservation in Washington (washingtonpost.com)

Another victim to rising labor costs has been plaster and lath. Although mold can grow on painted or dirty plaster under the right conditions, plaster does not support microbial growth because it is non-porous and lime-based or clay. The wood (lath) behind it, however, most certainly can harbor mold. (lookmold.com) In contrast, the drywall core of gypsum does not support microbial growth, but the outer paper facings do. Which is better? According to eSub, a construction software company, plaster is by nature a more durable finish than drywall, even high-level drywall finishes. In addition, plaster outperforms drywall in a number of key areas, including insulation, soundproofing, and fireproofing (instead of lath, modern plaster is set over a type of wallboard called blue board, which is similar to sheetrock at first glance, but it is specially formulated to handle high amounts of moisture in wet plaster, so it bonds tightly with the plaster.) Blue board is highly water and mold resistant. Therefore, in an older home with plaster and lath walls, it may be a good choice to repair the plaster and replace it in kind with new blue board and plaster (if you can find and afford the skilled craftsman to do so!).

Many older homes were “custom” homes, because they were hand-built by the owners. This can be good, or not so good, depending on the design experience of the builder. Today, “custom” homes demand a premium price, because unique plans, changes from pre-made plans and changes on site cost more money.

Whether your style is traditional or modern, the marriage of durable materials, good design and good construction is timeless! Make sure that any home you purchase or build has these characteristics and it can last for generations to come.

Photo by Ronnie Schmutz on Unsplash