Are Tiny Homes built from Sheds a Good Idea?

Are Tiny Homes built from Sheds a Good Idea?

At least every other day, I see an ad for a tiny home or office that companies or individuals built from what used to be backyard “sheds”. Now, don’t get me wrong, I am all for repurposing buildings and materials, when they are done the right way! (In fact, I even repurposed a large metal workshop building into a 2 bed/1.5 bath “condo” for my parents. This one is on a concrete slab and for all intents and purposes, could have been built that way as a home). What are the advantages, and what are the cautions, of making a home from a shed? (Many great points adapted from Living in a Shed: 9 Things (2023) You Must Know):

The advantages to living in a tiny home are many, for example:

- Up-front cost is cheaper than a house

- Smaller utility bill

- Less square footage to clean

- Less impact on the environment

- Privacy

- Portability

- Customization

- Ability to live in nature or “off-grid” more easily

However, “sheds” are only a subset of tiny homes, specifically, tiny homes that started out as prefab backyard buildings. Let’s take a look at what could go wrong from making one of these into a habitation.

First of all, when considering whether to build out a shed as a home, you should check into local building codes. If you live within city limits, there are likely laws about what type of buildings can be built or placed on your property to become “habitations”. Plopping a shed down and running electricity to it for your teenager to live in could be a big problem whenever it’s noticed by the building inspectors! Moving it to the middle of a few acres in the country doesn’t normally pose these legal issues, but again, it’s best to check with your local building inspector! If it’s illegal to live in a shed, it may be legal to live in an ADU-an Accessory Dwelling Unit. For example, ADU’s in California are required to be at least the size of an efficiency unit (at least 150 sq. ft. livable space plus a bathroom), they must contain a kitchen, a bathroom, they must be built on a permanent foundation, and must be able to turn on/off the ADU utilities without entering the primary unit. (ADU vs Finished Shed Comparison)

Construction: This is the largest area of caution we see. Within this topic, we need to highlight:

- Off-gassing of toxic compounds from interior building materials. If the building was never meant for habitation (even as a chicken coop!), then it may contain building materials that are rated for “outdoor use only” which may give off dangerous pesticides/weatherization chemicals.

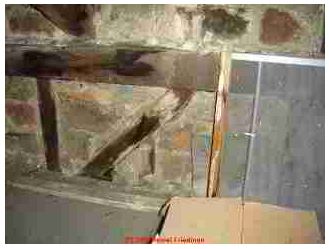

- Inferior flooring and framing techniques: We’ve seen them: sheds built to hold push lawnmowers and Christmas decorations may not hold up to daily living over a number of years. Holes or loose joints that develop inevitably allow pests to come in (they want to be cool/warm/fed too!).

- Inferior foundation: Setting a shed on a few cinder blocks is typically not sufficient for daily living and if the floor begins to sag, all kinds of structural issues (including leaks and mold) can ensue.

- Poor insulation: Typically, storage sheds only need to keep the paint from freezing, not keep a person comfortable, so insulation may not be optimal. This includes roof and floor insulation–yes, if your shed is not mounted to a slab foundation, it needs to be insulated!

- Improper sealing (which can cause moisture infiltration and mold growth): If siding is applied over the frame without an air or vapor barrier, it’s easy for moisture to condense inside the walls if they are heated for a living space, or similarly cooled during a hot summer. These steps in normal construction are what inspectors look for, for the safety of the homeowner and longevity of the building.

- Addition of water and sewage facilities warrants several considerations:

- Where is your water source and how will you deal with sewage? Sewage service is probably the biggest hurdle to overcome, as there are 3 options which may or may not be permitted in your locale: connection to the city’s sewer system, installing a septic tank, or installing a composting toilet.

- Plumbing in sinks, toilets, showers and drains also is done by code for a reason–leaks can cause serious mold and hygiene issues. It’s not a good idea to buy that shed if these appliances are added without proper spacing and materials by someone who knows plumbing code.

- Addition of power to the shed: Sometimes power service to a shed (50-100 amp service) is not what you would get for a normal home (200 amp service). Like the plumbing, wiring the shed for power should be done by someone who knows electrical code, so that it’s wired safely!

- Addition of HVAC to the shed: Sticking a “window unit” AC or space heater in the side of the shed may keep you cool or warm if it’s the right size, but without proper ventilation, you could build up CO2 and mold very quickly. CO2 is the product of insufficient ventilation, and face it, a shed is just a small, closed room unless proper ventilation is planned and built-in! The mold can result from simply living in that closed room, because along with CO2, every human exudes water vapor through their lungs and skin. If there are 2 people living there, the air quality will be even worse.

So far, it may sound like a major “NO” to use sheds as homes, but that’s just not true. If you’re allowed to use one in your locale, you can safely do so by starting from scratch (buying a bare-bones model) or buying one from a builder that knows good home construction. Then you can make sure that the construction, outfitting and customization will work for years to come without causing health issues. Let’s face it, home ownership is expensive, but saving on a tiny home just to live uncomfortably from lack of weatherization or get sick from mold is definitely not worth the savings. Therefore, planning is essential!

Photo by Andrea Davis on Unsplash