How to get free ventilation without sacrificing heat (or cool)

Something has piqued my interest for some time: the transfer of heat to make something cooler or warmer than the ambient air without mechanical means. Living in the hot and humid southeast US, I’m keenly aware that air conditioning is key to my comfort during the summer. Ventilation is necessary, but ventilation will make my house hot like the outside…or will it?

I’m going to draw on a 2023 study that showed how to ventilate a building by natural means (no fans) but still cause it to be 7 degrees cooler than the outside, even with an internal heat source. Whoa! This is noteworthy.

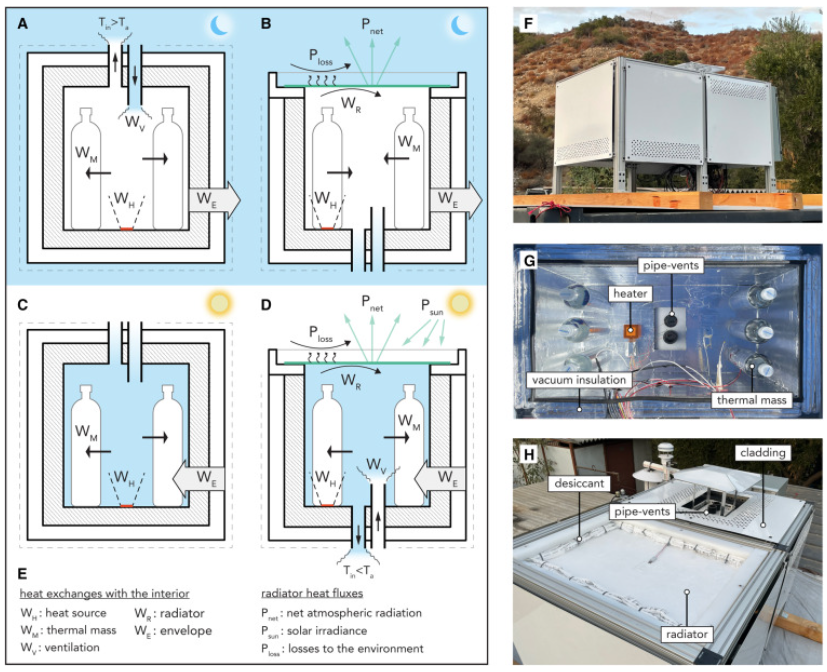

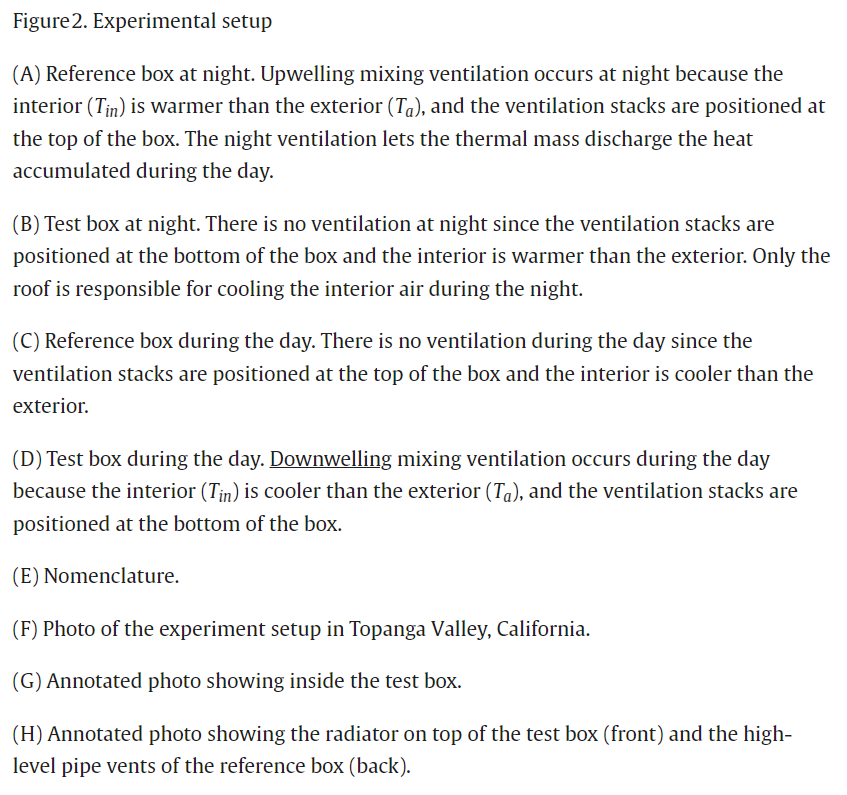

I’ll give you the simplified version. The study involved placing 2 insulated boxes on the top of a shipping container in a warm, dry climate (Topanga Valley, CA). The “reference” box had insulation on all 6 sides. The “test” box had insulation on the four vertical sides and bottom, but for the top had an aluminum plate on which a radiant material was glued. The only ventilation in each box was 2 PVC pipes. On the reference box, the ventilation pipes were in the top of the box, while on the test box, they were in the bottom of the box. Each box contained (4 to 6) 1-liter water bottles for thermal mass, as well as a small heater to simulate lighting, fans and other electrical loads that would be operating in a home.

What happened in these boxes? The differences of a) removing the insulation from the roof and replacing it with conductive and radiative materials, as well as b) placement of the ventilation pipes, caused a substantial difference in the way the boxes ventilated and their interior temperatures. Here’s a schematic of the boxes:

In a nutshell, this type of natural ventilation is driven by differences in temperature. During the day, the reference box did not ventilate because the interior stayed cooler than the exterior. It only ventilated at night, because with cool desert temperatures at night, the interior was relatively warmer than the exterior. However, the test box actively ventilated during the day because the cool air in the box sank out through the ventilation pipe on the bottom, and was replaced with warmer air. However, it stayed cooler than the reference box because the conductive material on the roof (aluminum) drew heat from the inside and the radiative material reflected 93% of solar heat back into space. Here’s a summary of the benefits of the test box setup:

There was a net loss of heat during the day and the night, even with an internal heat source.

Ventilation during the day occurred 7 times per hour (7 ACH).

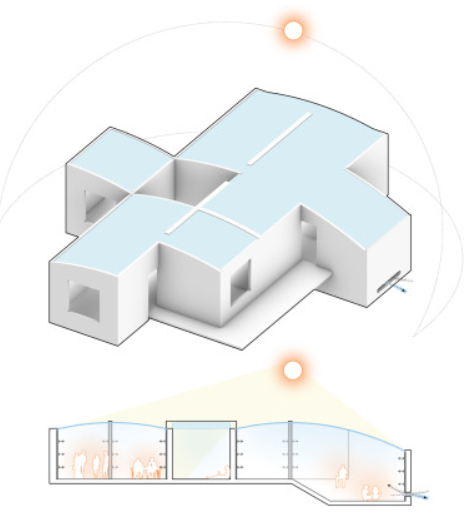

Here’s an architectural concept of what a real house could look like:

Other details:

- The reference box only ventilated at night and the test box only ventilated during the day. In a real building, however, both ventilation approaches can be combined to produce continuous ventilation, switching between downwelling and upwelling by activating different vents as necessary.

- The thermal mass inside the boxes had the purpose of modulating heat fluctuations.

- The insulation used on the boxes was vacuum panels, which are a very effective insulation, albeit an expensive one for residential housing!

- Convection shields of metal with a radiative coating were placed over the sides of the boxes to prevent them from absorbing solar heat.

- The boxes had no penetrations except for the ventilation pipes, which is not a realistic residential scenario with no windows or doors.

- The boxes were tested in a warm dry climate, without humidity/mold concerns. In a more humid climate, dehumidification would probably be necessary.

- Ventilation pipe size and thermal mass would need to be fine-tuned for each home and its occupants.

- Removing the roof insulation from a modern home is quite unusual; in fact, a previous version of movable roof panel insulation and radiant covering was key in Harold Hays’ Skytherm innovation.

Wow, this is really quite fascinating. Imagine having copious ventilation AND keeping your home cool in the summer. Windows don’t have to be heat loss/gain devices, either: with new insulation materials coming into existence all the time (there’s a new aerogel made from cellulose that’s even more transparent than glass), or the Parans solar lighting system that captures sunlight and sends it indoors via fiber-optic cables, a super-insulated, light-filled home is possible (with the right budget). The idea of thermal mass is certainly not new, either; that’s the reason stone and earth have been used in warm-climate homes for millenia! We also wrote about a new insulation material that uses phase-change to absorb heat without transmitting it into your home. With the invention of new radiant systems like the SkyCool system, buildings are actively rejecting solar heat and removing heat from inside the building, saving from 15-40% of cooling costs.

Even without the high-tech materials, the main takeaway of this concept is to seal up your home and ventilate naturally: to do this in warm climates it’s best to have the ventilation intakes lower in the house, on the “cool” side. Also, look into a radiant barrier for your attic space; we give some tips in this article. Finally, always monitor humidity, no matter the temperature. No one can live in an ice-box and turn a blind eye to humidity and mold!

Photo by frank mckenna on Unsplash